[Originally written December 9, 2019 for Dr. Aimée Morrison, University of Waterloo, Imported from my old website on August 8, 2024]

Children’s Consent, Digital Representation, and Privacy in the Age of Accessible Social Media

Acknowledging situated knowledge

When I want to figure out what to buy one of my five younger siblings for birthdays or other holidays, I Google “Gifts for [insert demographic here]” and I find actual children from that age grouping voicing their recommendations. I know that this practice is helpful, especially when you feel lost trying to buy something age-appropriate or don’t know what is considered trendy for that group right now, but what does this mean in the grander scheme of things?

By listening to the opinions, endorsements, and reviews made by kidfluencers, I can get a sense of the values and interests of a demographic of which I am not a member, and that is something valuable. Are there any issues with this practice?

In this post, I offer a discussion about children on social media, commentary on the rise of the kidfluencer, and critiques of mismanaged consent, digital self-representation, and privacy practices performed on behalf of children without their involvement.

I wanted to connect this research back to my own research interests in popular culture studies, so I have situated kidfluencers to child actors and I question how we might approach this emerging field differently to not repeat past incidents of the mismanagement of children’s rights and representations.

Where and how do children fit on social media?

How do we navigate children’s digital representation and privacy in the age of accessible social media? Using Laurie McNeill and John David Zuern’s methodology in relation to generous reading of digital lives, how do we maintain curiosity among reluctance (McNeill & Zuern 2019)? That is, how do we find the merit in the field without only imposing our judgement on it?

Social networking sites have been taken advantage of as user-generated content creation platforms and processes, where content can be easily produced and quickly distributed by:

Participants who are interested in their digital self-representations, and;

Companies who are interested in user-generated branding (Burrman 2010).

Among these users are child influencers – affectionately named “kidfluencers” – whose accounts play a crucial role in social media advertising and marketing, especially in terms of children’s toys and products (Attwood & Elton 2003).

Children being included in discussions on social media is an exemplification of changing and expanding social media environments: the use of social media for advertising purposes has proven to be quite lucrative, the creation of hashtags has formed online communities between groups with similar life experiences or interests (including commercial interests), and the proposition that children can be legitimized as consumers of both media and products in their own right.

"The parent said brands might pay $10,000 to $15,000 for a promotional Instagram post while a sponsored YouTube video might earn $45,000. A 30- to 90-second shout-out in a longer video can cost advertisers between $15,000 and $25,000."

— Parent of a popular (unnamed) kidfluencer, interviewed by Sapna Maheshwari (2019)

The hashtag, #kidfluencer, on Instagram leads to shared spaces for children and the parents of children to produce selfies as an expression of both consumerism and community-building. The policy-ordered “run by my parents” aspects of children’s social media accounts, however, reveal an emerging issue of consent and privacy being decided and declared on behalf of children, rather than in collaboration with them (“Tips for Parents” 2019). So, although the kidfluencer field does have merit and children can be very successful as influencers, the general mechanics that go on behind the scenes of the construction of kidfluencers’ digital representations are complex and thus are often subject to criticism (Atkinson 2019).

Recognizing and acknowledging that kidfluencers have already proven to be particularly successful at courting audiences and making money on social media, there is an immediate need for restructuring the conversation about the protection of privacy and consent practices in terms of children’s digital representations. What is ethically at stake when we share intimate details of children’s lives in real-time? Similar to improperly managed cases of child actor practices on the side of parents, the kidfluencer field is susceptible to the same detrimental effects on children if not reconceptualized to prioritize the children involved (Lopez 2014).

Direct primary examples of kidfluencers on Instagram

The kidfluencer accounts and selfies I chose to look at in-depth exemplify either the phenomena of using and targeting children as consumers and marketers or the creation of children’s digital identities as controlled by parents.

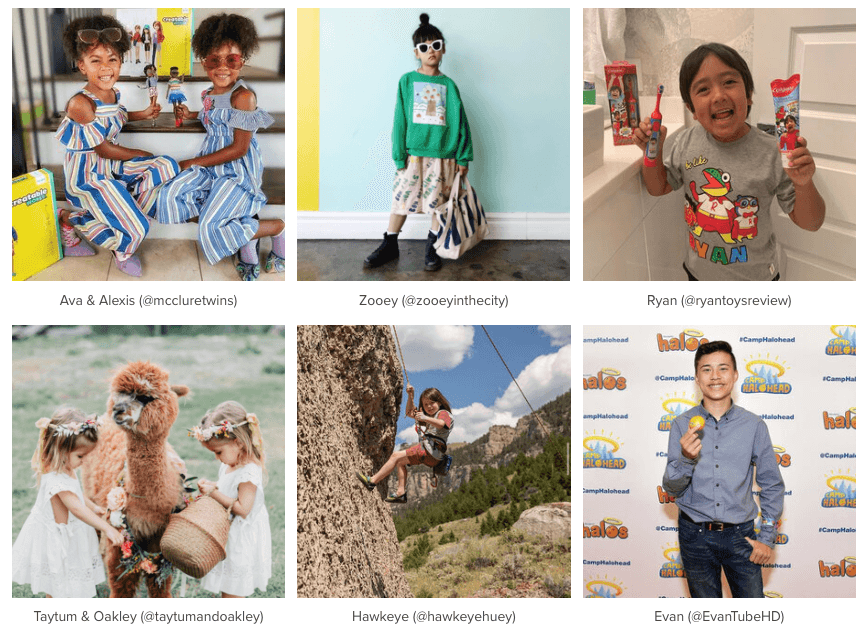

Below is a sample of kidfluencers, emphasized as being “need-to-know” when familiarizing yourself with the kidfluencer community (Medeiros 2019):

Kidfluencer selfies appear highly staged and stylized, often featuring both the children and an object of advertisement within the photograph’s frame. Some accounts’ selfies are heavily filtered to maintain cohesion throughout their feed. Many are taken by parents.

This project was initially inspired by my own brother’s fascination with Evan of EvanTubeHD (pictured above, bottom-right). My brother would watch Evan play with and review toys on YouTube almost obsessively, even when he already owned the toys being featured in such videos himself.

Observing his behaviours prompted me to think about what compels people to follow in the footsteps of influencers, however, this case is a little more difficult to understand: how have children suddenly become tastemakers, too?

What happens when we consider children as consumers and tastemakers?

The rise of the kidfluencer prompts discussions about the development of children into consumers and tastemakers, especially on platforms where they are too young to sign up for themselves according to platform policies.

What made eight-year-old Ryan ToysReview the top earner on YouTube of 2018, grossing $22 million and surpassing popular adult YouTubers (like Logan and Jake Paul, Dude Perfect, and PewDiePie) (O’Kane 2018)? Inspired by other children on YouTube, Ryan created his channel in 2015 and as of 2018 “ha[d] over 25 billion views in total and 17 million subscribers… Forbes reports he now has his own line of collectables selling at Walmart” (O’Kane 2018).

This isn’t a one-off occurrence. Children regularly occupy online spaces as product reviewers and marketers. See for yourself under #kidfluencer Recent Posts on Instagram.

Companies regularly reach out to children and offer them endorsement deals in exchange for an advertisement:

Mayhem, a 4-year-old dress-maker, was asked to collaborate with popular clothing company J.Crew to produce a children’s clothing line (Choi & Lewallen 2017).

Fifteen-year-old Jojo Siwa has endorsement deals and sells two branded apparel lines with Target Corp., the second-largest U.S. retailer (Bergen 2019).

Advertisers like Walmart, Staples and Mattel are “bankrolling lucrative endorsement deals for toddlers and tweens with large followings and their own verified profiles on YouTube and Instagram” (“Who are online, recruited by advertisers and 4 years old? Kidfluencers” 2019).

The fact that advertisers are employing kidfluencers as social media marketers leads to questions about how they might be targeting their marketing toward other children they know are on such platforms (although policy-wise they should not be). How ethical is it to expose young followers to such marketing when they may not recognize it as marketing at all?

Kidfluencers are the new child actors

“I don’t want to have a child 15 years from now sitting in a therapist’s office saying my parents made me take pictures every day,” kidfluencer mother Bee Fisher says. “If there’re days they’re totally not into it, they don’t have to be… unless it’s paid work. Then they have to be there" (Ellis 2019).

The micro-celebrity status of children on social media has situated kidfluencers as the new child actors. Reminiscent of early Hollywood, financial management and responsibilities for the determination of consent lay on the shoulders of parents. People are producing revenue using their children, and financially important activities have the potential to lead parents to act based on promised income rather than family cohesion.

Will kidfluencers feel the same way child actors have? Think of the exploitation the following iconic Hollywood child actors, to name a few, have faced:

Judy Garland: “[Louis B.] Mayer insisted she consume only black coffee and chicken soup, plus 80 cigarettes a day and pills every four hours to quell her appetite” (Wilson)

Shirley Temple: “You can imagine the surprise of Shirley Temple, an adult at the time, when she discovered her accounts only showed $44,000 instead of the $3.2 million she had earned” (Lopez)

Lindsay Lohan: “The established narrative about Lohan was written long before she was old enough to start contributing to it herself… Lohan was likely keeping the family afloat financially — merely a tool in their ongoing divorce and attempts to become rich and famous” (Koul)

Nevertheless, at least in the child-acting field, attempts are being made to protect children (e.g. court-ordered trusts and union rules) to prevent exploitation from bad parents or bad movie industry practices; no such rules or regulations apply to kidfluencers yet. The California Coogan Law, for instance, was implemented to responsibly protect a reasonable amount of child actors’ earnings until they enter adulthood; at eighteen years old, the child actor gets access to their Coogan fund, as well as legal control over their entire income (Wallace 2019). The Coogan law also outlines compulsory education laws (so that the child actor’s education should not be interrupted by work) and working hour labour laws (to prevent children from working too many hours in a day) (David 2019).

I definitely think there has been a lack of research done in terms of how social networking sites influence the mental well-being of young children, a demographic left out of these kinds of studies because of social networking sites’ age restriction policies, and that this neglect needs to be addressed.

Nadine Davidson-Wall discusses this in ‘“Mum, seriously!”: Sharenting the new social trend with no opt-out” that there have been studies done about the effects of social media on the self-concept of teenagers and adults, and many of such studies have been negative (e.g. depression and low self-esteem connected to the approval-seeking practice of social networking sites) (9).

Although we do not yet have solid research done in this area concerning younger children, I can note a few kidfluencers that have already burnt out on their platforms due to the content-production demands placed on them by both viewers and parents. They also often cite not having a proper adolescent experience as a reason for wanting to take a break from production.

Ethan and Grayson Dolan had produced a new video on YouTube every week for years. Then, they posted a video titled “It’s Time To Move On” where they spoke candidly about their mental health, the pressure to create content, and only being able to take off a month after their father’s passing because they felt pressured to return to work (Bonner 2019).

After eight years of posting content, Canadian creator Lilly Singh announced that she needed to take a break to focus on her mental health. She said, “I’m not at my optimal happiness right now, I could be mentally healthier. I don’t feel like I’m completely mentally healthy. There’s a lot going on up here that I need to address and I’m not able to constantly pumping out content” (Connellan 2018).

YouTuber Elle Mills posted a seven-minute confession about her unhappiness, stating that “she couldn’t keep up with the pressure, and told her friends that while she was safe, and in good hands, she needed time to recuperate and remember why she loved making videos in the first place” (Alexander 2018).

More and more of YouTube’s top creators are coming forward with similar experiences, and so I think it is important to consider the implications of pushing children into the public eye so early in life. There is no structure regarding how many hours should be worked, what type of care you should be taking for yourself and your body, education on stress-management techniques, etc.

Instead, children are being taught to prioritize endorsement deals and the maintenance of their online relevancy, and this is a major concern of mine. It’s one thing for children to have fun making videos and reviewing toys, but it’s another for them to feel as though they’re sacrificing their mental well-being or childhood experiences for it.

Discussion of ethics

What right do parents have to control and construct their children’s digital representations, especially without considering how their data might be archived/stored in databases for an unidentifiable amount of time?

Instagram’s Privacy and Safety Center states that Instagram requires its users to be at least thirteen years old before they can create an account, and that “accounts that represent someone under the age of 13 must clearly state in the account’s bio that the account is managed by a parent or manager” (“Tips for Parents” 2019). I feel as though this practice, although not its primary intention, forces parents into determining consent on behalf of their children, and pushes for the removal of agency from children regarding the creation of their own digital identities.

Julia Watson and Sidonie Smith (2014) in Virtually Me discuss the “permanence” of online tidbits of the self: “online users are implicated in contributing user-generated content, which can return in digital afterlives, as online archives and databases become ever more searchable” (73). Smith and Watson also question the ethics of going public with material about family and friends in the context of self-presentation and appropriating materials from other people’s lives (81). I, too, feel as though there is a need for conversations about digital ethics practices in this newly developing field. The circulation of online life-writing is unpredictable and unstable, so I’m not surprised that there is concern about whether or not old kidfluencer content might resurface later on in children’s lives.

I also question the ethics of exposing other children on social networking sites to marketing when they’re too young to recognize that they’re being advertised to.

One kidfluencer father, Adam Ali, states that his daughter, Samia, “can’t verbatim get the message out. Sometimes [companies’] talking points are not kid talk, so [Samia’s mother or himself] would need to appear to relay those because those are key deliverables that the brands want” (“Who are online, recruited by advertisers and 4 years old? Kidfluencers” 2019). When the kidfluencer’s thoughts are scripted, so much so that they can’t get the words out themselves, is video-making still fun? While children under the age of 13, as mentioned, are not supposed to be on Instagram, we know that they are. So do companies. Children who cannot recognize advertising strategies are at risk of being manipulated by companies targeting them for or in their marketing.

Conclusions

We need to reconsider kidfluencer practices that do not prioritize the children creating the content. The current ideology, that parents and companies can have all the money with none of the worries or responsibilities, is insufficient. While there may not be a need for formal agent representation and financial advisors, as with child actors of the past, this does not mean there should not be discussions around the ethics of digital representation and management of children.

How do we protect children’s privacy and consent in online spaces? How do we legitimize children as consumers and advertisers without exploitation (of them, or of their peers being subject to their advertising)? How do we prevent further burnout at such young ages? These are all important questions that we need to turn our attention to as the kidfluencer field continues to grow.

References

🦄 Mommy/Daughter LOL Surprise👭 (@kbtoyreviews) • Instagram Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/p/B5X2wtxHax8/. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

Alexander, Julia. “YouTube’s Top Creators Are Burning out and Breaking down En Masse.” Polygon, 1 June 2018, https://www.polygon.com/2018/6/1/17413542/burnout-mental-health-awareness-youtube-elle-mills-el-rubius-bobby-burns-pewdiepie.

Atkinson, Nathalie. Beware the ‘Momager’: Why Parents Shouldn’t Cash in on Cuteness. The Globe and Mail, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/style/article-beware-the-momager-why-parents-shouldnt-cash-in-on-cuteness/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

Attwood, Jonathan, and Emily Elton. “Taking Kids Seriously as Influencers and Consumers.” Young Consumers, Sept. 2003. world, www.emerald.com, doi:10.1108/17473610310813942.

Bergen, Mark. “YouTube Kidfluencers Are Becoming Minefields for Google.” Fortune, https://fortune.com/2019/03/23/youtube-influencers-kids-marketing/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

Blum-Ross, Alicia, and Sonia Livingstone. “‘Sharenting,’ Parent Blogging, and the Boundaries of the Digital Self.” Popular Communication, vol. 15, no. 2, Apr. 2017, pp. 110–25. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1080/15405702.2016.1223300.

Bonner, Mehera. “The Dolan Twins Tearfully Reveal They’re Stepping Back from YouTube.” Cosmopolitan, 9 Oct. 2019, https://www.cosmopolitan.com/entertainment/celebs/a29410035/did-dolan-twins-quit-youtube/.

Burmann, Christoph. “A Call for ‘User-Generated Branding.’” Journal of Brand Management, vol. 18, no. 1, Sept. 2010, pp. 1–4. Springer Link, doi:10.1057/bm.2010.30.

Choi, Grace Yiseul, and Jennifer Lewallen. “Say Instagram, Kids!”: Examining Sharenting and Children’s Digital Representations on Instagram: Howard Journal of Communications: Vol 29, No 2. no. 2, July 2017, pp. 114–64, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2017.1327380.

Connellan, Shannon. “YouTuber Lilly Singh Is Taking a Break to Focus on Her Mental Health.” Mashable, https://mashable.com/article/lilly-singh-takes-break-from-youtube/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

David, Ben. Labor Laws for Child Actors. https://yourbusiness.azcentral.com/labor-laws-child-actors-9025.html. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

Davidson-Wall, Nadine. “Mum, Seriously!”: Sharenting the New Social Trend with No Opt-Out. 2018, p. 11.

Ellis, Emma Grey. “Child Stars Don’t Need Hollywood. They Have YouTube.” Wired. www.wired.com, https://www.wired.com/story/age-of-kidfluencers/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

Fisher, Lauren Alexis. “J. Crew Taps 4-Year-Old Designer For Kids Collection.” Harper’s BAZAAR, 9 Dec. 2014, https://www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/fashion-designers/j-crew-mayhem-4-year-old-designer-crewcuts-collection.

Jumble21 (@jumble.21) • Instagram Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/jumble.21/. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

#kidfluencer Hashtag on Instagram • Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/kidfluencer/. Accessed 21 Oct. 2019.

Kidfluencers | Work With The Best Kid Creators. https://www.kidfluencers.com/. Accessed 21 Oct. 2019.

Little Red World (@littleredworldofficial) • Instagram Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/littleredworldofficial/. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

Lopez, Destiny. “7 Celebs Whose Parents Decimated Their Fortunes.” Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/7-celebs-whose-parents-decimated-their-fortunes-2014-4. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

Maheshwari, Sapna. “Online and Making Thousands, at Age 4: Meet the Kidfluencers.” The New York Times, 1 Mar. 2019. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/01/business/media/social-media-influencers-kids.html.

Maya Moonicorn (@maya_moonicorn) • Instagram Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/maya_moonicorn/. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

McClure Twins - Ava & Alexis (@mccluretwins) • Instagram Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/mccluretwins/. Accessed 21 Oct. 2019.

McNeill, Laurie & Zuern, John. (2019). Reading Digital Lives Generously. 10.4324/9780429288432-18.

Medeiros, Madison. “The Biggest ‘Kidfluencers’ You Need to Know.” SheKnows, 12 June 2019, https://www.sheknows.com/parenting/articles/2044537/biggest-kid-influencers/.

O’Kane, Caitlin. Top 10 Highest-Paid YouTube Stars of 2018, According to Forbes. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/top-10-highest-paid-youtube-stars-of-2018-forbes/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

Paige XOXO (@paigexoxochannel) • Instagram Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/p/B5UiQdEnoMb/. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

Patience (@patiences_magical_toy_emporium) • Instagram Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/p/B4aMS8nH-ft/. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

#sharenting Hashtag on Instagram • Photos and Videos. https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/sharenting/. Accessed 21 Oct. 2019.

Steinberg, Stacey B. “Sharenting: Children’s Privacy in the Age of Social Media.” Emory Law Journal, no. 4, 2017 2016, pp. 839–84.

“The Rise of ‘Kidfluencers’ and ‘Sharenting’: Cause for Concern?” Intellectual Takeout, https://www.intellectualtakeout.org/article/rise-kidfluencers-and-sharenting-cause-concern. Accessed 21 Oct. 2019.

Tips for Parents | Instagram Help Center. https://help.instagram.com/154475974694511. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

Tur-Viñes, V., et al. Kid Influencers on YouTube. A Space for Responsibility. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 28 June 2018. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.4185/RLCS-2018-1303en.

Wallace, Bonnie. “Who Gets the Money When a Child Actor Works?” Bonnie J. Wallace, 27 Jan. 2016, https://bonniejwallace.com/who-gets-the-money-when-a-child-actor-works/.

Who Are Online, Recruited by Advertisers and 4 Years Old? Kidfluencers - TODAYonline. https://www.todayonline.com/world/who-are-online-recruited-advertisers-and-4-years-old-kidfluencers. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

Watson, Julia, and Sidonie Smith. Virtually Me: A Toolkit about Online Self-Presentation. www.academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/14945140/Virtually_Me_A_Toolkit_about_Online_Self-Presentation. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.