[Originally written December 3, 2019 for Dr. Aimée Morrison, University of Waterloo, Imported from my old website on August 8, 2024]

Prewriting analysis and rhetorical choices

Before beginning to take the photographs for this assignment, I had a few decisions to make.

First, I had to decide which “self” I wanted to foreground.

I chose to focus my Selfie Assignment on an aspect of my life that demands the most time and commitment overall – my role of being a dog mom to my Miniature Dachshund puppy, Stanley. I came to this decision by acknowledging that it would be the most practical area of my life to produce content from, seeing as I would not necessarily have to leave my neighbourhood or do anything outside of my normal routine to get the pictures I wanted; I walk, play, and take photographs of any other interactions with Stanley religiously and somewhat obsessively already.

I argue that the photographs I have shared of my dog are still selfies because I have either featured parts of my own body in them, was the one holding his leash, or meticulously staged the images myself. I rationalized these arguments by looking back at our class notes, where we suggested that when the person’s face is absent from the selfie, a selfie could also be something the person is engaging with, a personal and individual experience, or some component of the person’s identity or location. I would say that the twelve selfies I have taken with my dog satisfy these criteria.

I decided that I wanted to tell a story about myself outside of academia or work, because I value my personal life, but not many people outside of my family or close friend group get to see that side of me regularly. I think that in the last few years being overly private with the intimate details of my personal life has been a downfall of mine, so I thought this assignment would be a good way to begin to share more of the little moments that my peers otherwise would not see.

Nevertheless, I still like to have some sort of control over who gets to view and interact with my content online, especially on Instagram. My own Instagram account is private and limited to an audience that I approve of. Out of personal preference, I choose not to share images of my face on Instagram feeds outside of my own or my close friends’ private Instagram accounts.

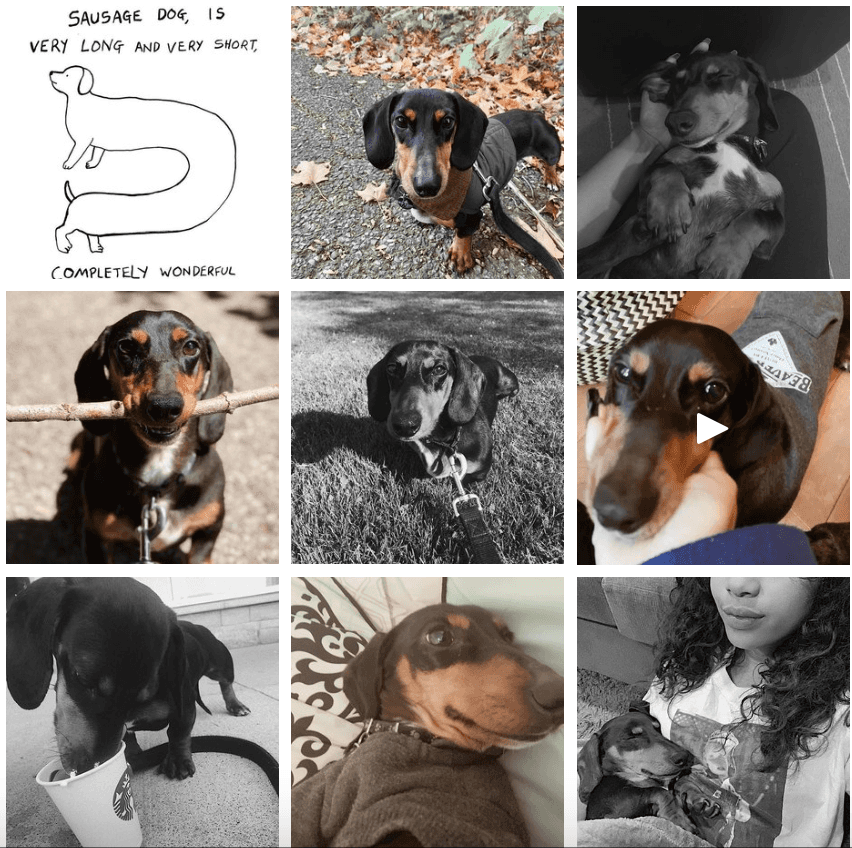

So, I decided to demonstrate selfie practices for this assignment by featuring my dog, and also either only partially showing my face (without tagging myself) or having only my hands featured on Stanley’s public feed. In some ways, I maintain anonymity on the @AWeenieNamedStan public Instagram account while still creating some sort of digital self-representation; I was able to share images of my daily routine, including moments of leisure or humour, without explicitly giving away any connection to my academic or work life.

Next, while I had already been leaning towards creating an Instagram account for this assignment, I had to determine what social media platform would actually be most appropriate for the content I was trying to create, and the type of audience I was trying to court.

I had to rule out Facebook sharing because of their real-names policy, which restricts users from pretending to be anything or anyone. Your Facebook name has to match your ID or be some logical variation/nickname of your official government name (e.g. using the name Bob instead of Robert) (“What names are allowed on Facebook” 2019).

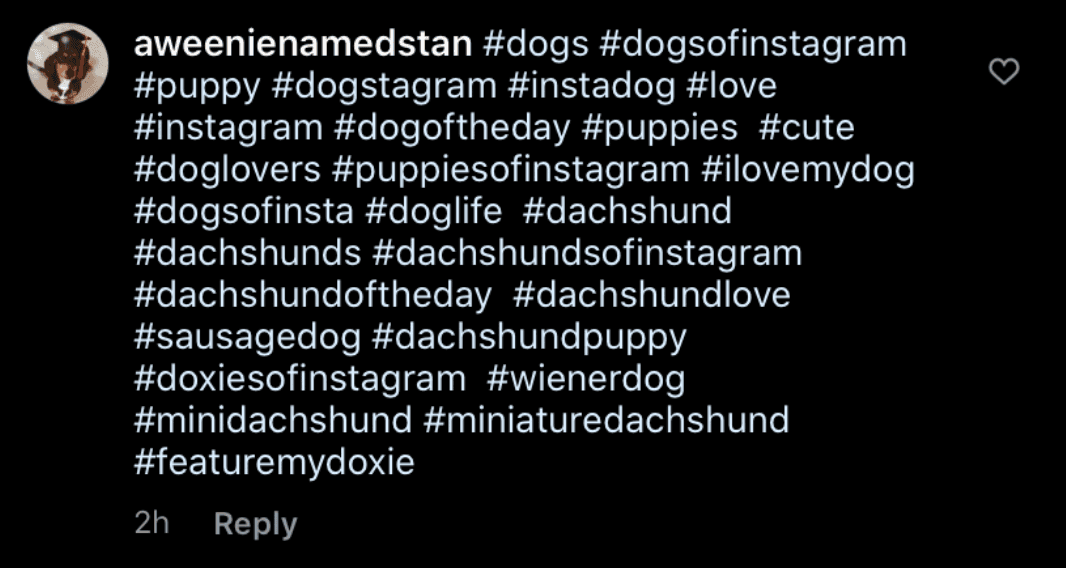

When deciding between the other major social media networks, I chose to use Instagram simply because, from experience, I know there already exists a large demand for dog photographs on Instagram. After doing some searching through communities to participate in on Instagram, I found that #dogsofinstagram comprised over 164.3 million posts. Even further, #dachshund had over 12.2 million posts.

Since I was seeking to court a mass (but still pretty niche) audience of dog lovers and dog accounts, Instagram seemed like my best option for achieving what I wanted out of this assignment. To gain some headway in creating a follower base for Stanley’s account, I began to post and engage within the Dogs of Instagram and Dachshund Instagram communities by liking and commenting on posts. I also followed over 200 dog accounts, some of which were recommended by Buzzfeed as must-follow “dogfluencers”, in hopes that they or some of their followers would explore my page and follow me back.

Since I chose to post on Instagram, I made several rhetorical choices to adjust my content to be appropriate to the medium.

I acknowledged that cute photographs of dogs on the internet, in my opinion, are already pleasurable and fun, but I did want to integrate a thoughtful use of aesthetics into this account as well. I know that Instagram posts are largely reliant on visuals, so I used emojis in the account’s biography and caption sections to break up any strings of text. I also created a cohesive Instagram feed theme, alternating between overlaying black-and-white and brown-toned filters (which I edited and imported from the VSCO application on my phone). When you look at the account as a whole, you can tell that the layout of the account was thoughtfully planned; this carefully curated approach to posting content on Instagram is different than posting on Snapchat or Twitter – platforms that do not present your content in a tiled and unified way, but instead as individual and standalone postings.

Challenges and outcomes

One aspect of running a dog Instagram account that I found to be different than running my own private account was that driving engagement to my content was much more difficult and at times far more impersonal and robotic.

On my account, I can expect to usually get likes and comments from a handful of friends, family, and acquaintances that I have built some sort of personal relationship with. I hardly – if ever – use hashtags on my personal account because my page still would not be visible to the greater population of Instagram users due to my restrictive privacy settings, so I had to adjust my posting strategies for the sake of this project.

On Stanley’s public account, I found that most of my likes came from non-followers who found my page from exploring the hashtags, and most of the comments or direct messages Stanley received seemed like automated responses designed by companies or other pages to garner engagement to their accounts (see the Artifacts PDF for some examples). After following over 200 dog accounts and reaching over 100 followers, I still did not see much growth in the amount of likes I was getting per post. I decided that perhaps it was more important to make my posts visible to as many people as possible by using hashtags rather than trying to get likes from my following.

Another practice within the Dogstagram community that I found particularly interesting was the abundance of direct marketing targeted at new accounts with small followings.

I would not necessarily consider Stanley or his account “influencer material” in any right with his 100 followers, but still, I received messages almost daily from dog merchandise companies or other dog accounts either looking for followers or offering me commission or discount opportunities for buying and sharing their products. This contrasts the typical view of human Instagram sponsorship, where we think only beautiful people doing extraordinary things with thousands if not millions of followers are deserving of #ad opportunities.

There is something so marketable about cute animal photographs on the internet, and from the weeks of running Stanley’s account, it seems as though because of this it takes a lot less effort to be successful in this sense as an average dog on Instagram than an average person.

Critical analysis

Where, at least outside of poetry, the visual aesthetics of life writing as found in autobiographies, memoirs, and biographies is not necessarily equally or more important than the text itself, the same is not true when sharing personal images. When we analyze the context of personal images, we consider all of its parts – the composition of the image itself, the caption, the date stamp, the hashtag, the tagged subjects of the photograph, etc. When we analyze personal writing, the text and title generally speak for themselves without the need for further context. For instance, in an autobiography, I might write that as a child, I used to go to the park by my home every day after school, and that generally tells a reader all they need to know to get a basic understanding of my personal experience. On my Instagram, I might share a photograph of me at the park and caption it #ThrowbackThursday. It might seem strange that I, a grown woman, would post a picture at the park on a work night, but with contextual clues like a location tag within my neighbourhood, personal tags within the photograph directed to the friends I used to share that space with, or even understanding the meaning of the hashtag as referencing something from the past, you can build a complete story of the image.

In a sense, the stakes of sharing personal images rather than personal writing are different depending on what you are trying to achieve. Straightforwardness for story-telling purposes, in general, is easier in personal writing because you explicitly outline what you want the readers to interpret from your text directly within your text.

On the other hand, less direct personal images require some clues and strategies to be analyzed together to be fully decoded and contextually understood. This analysis reminded me of our in-class discussions of what constitutes a selfie (the camping image). While the image itself tells part of the story behind the image, the situation is more well-developed after considering the caption: “Prepping my grad class on platform, software, coaxing, coaching, accordance, constraint. Rainy morning at the campsite. Yacht Rock and Deep Woods Off. Little kids on bikes, the sounds of breaking camp”. We get a glimpse of context from the can of Off Bugspray in the background of the image, but we get to understand the individual experience and moment being captured through other resources connected to the photograph or other information found on the poster’s account supporting the image.

In terms of courting and maintaining an audience, Stanley’s Instagram account largely reflects many of the other dog accounts that I explored in my research for this assignment. I found a non-academic blog post on how to easily create a following as a dog account and followed it almost exactly because I thought it would be important to do what the community expected in terms of content if I wanted to get likes and followers (Kledzik). I observed dog accounts in practice and tried to mimic some of the strategies that they used in my approaches to posting and creating content (e.g. posting consistently, taking advantage of editing apps, trusting the power of hashtags, engaging with other people within the same community, etc.).

In less than two weeks, I gained over 100 followers and have not lost any; I would predict that the numbers would continue to increase and stay fairly balanced if I kept up with the account in the coming weeks, and I would accredit this to being strategic in my use of the account. To court and maintain an audience in general is to analyze how best to increase visibility and engagement from the audience you want, and to continue to use these approaches even after gaining somewhat of a following to keep the followers you have gained interested in the future.

Ultimately, I had mixed feelings about the process and outcome of this selfie project. Perhaps my experiences with dog Instagram accounts would change if Stanley were to gain a large following (and most of the account’s engagement came from real followers), but for now, I find the mechanics of “dogstagrams” quite robotic. I am still not entirely sure if any of the comments on my posts are genuine because of how generic they are. To me, relying so heavily on hashtags and automated follows to drive engagement seems counterproductive in the search for sharing intimate details of life with the masses. I do think that I have entered uncharted territory, so to speak, in the sense that I have used a specific platform in a new way with new content using new strategies to reach a new audience.

However, I think the project failed in the sense that I do not think I have gained any sort of meaningful new relationships with any “peers” from sharing this side of my life like I thought I might. I suppose an affordance of Instagram as a platform that I overlooked was that robotically controlled user accounts would have the opportunity to engage with my public content just as often, if not more often, as real people. Certain Instagram users found ways to navigate the algorithms to get the most engagement possible within their communities, which further explains the copy-and-paste type direct messages and comments I received on @AWeenieNamedStan. Although I was putting a lot of effort into the account personally and creatively, I did not find that I received such personable content back from my followers throughout this assignment. I still find this whole robotic process more disingenuous than my process of gaining followers on my account, but if one’s purpose is to gain a large following in a short amount of time, I can see the merit in participating in it; my intended purpose for Stanley’s account was different, so next time I might try a different approach.

References

Courtney. “21 Things Only Single Dog Parents Understand.” BarkPost, 7 Nov. 2013, https://barkpost.com/humor/25-signs-that-you-are-a-single-dog-parent/.

Fontein, Dara, and Kaylynn Chong. 8 Dogs That Are Better at Instagram Than You. https://blog.hootsuite.com/dogs-of-instagram/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.

Kane, Kiki. These Excellent Dog Bios Are So On-Point You Can’t Help but Laugh | The Dog People by Rover.Com. https://www.rover.com/blog/excellent-dog-bios-point-cant-help-laugh/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.

Kledzik, Kristina. “How to Make Your Dog Insta-Famous & Use Instagram to Do Good for All Dogs.” The Dog People by Rover.Com, 22 May 2017, https://www.rover.com/blog/make-dog-insta-famous-use-platform-good-dogs/.

Lieber, Chavie. “Instagram Can Make Your Pet Famous — and You Rich.” Vox, 6 Nov. 2018, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2018/11/6/18066056/dog-instagram-famous-pet-influencers.

Morrison, Aimée. “Aimée Morrison on Twitter: ‘Prepping My Grad Class on Platform, Software, Coaxing, Coaching, Accordance, Constraint. Rainy Morning at the Campsite. Yacht Rock and Deep Woods Off. Little Kids on Bikes, the Sounds of Breaking Camp. Https://T.Co/TKlxnpYVtg’ / Twitter.” Twitter, https://twitter.com/digiwonk/status/1175769495576698881. Accessed 11 Oct. 2019.

Norman, Don. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition. Basic Books, 2013.

O’Sullivan, Kelly. “These Dog Instagram Captions Are Perfect for the Cutest Photos of Your Furry Friend.” Country Living, 18 July 2019, https://www.countryliving.com/life/kids-pets/a28423224/dog-instagram-captions/.

Pepe, Gian. “How To Make Your Dog Instagram Famous in 10 Weeks or Less.” Jumper Media, 14 Apr. 2019, https://jumpermedia.co/how-to-make-your-dog-instagram-famous/.

Photo Prop For Dogs by Pooch Selfie | The Grommet®. https://www.thegrommet.com/products/pooch-selfie-prop-for-dog-photos-selfies. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.

Piedra, Xavier. The Best Dog Accounts on Instagram to Get Your Fluff Fix. https://mashable.com/article/best-dogs-of-instagram/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.

Semigran, Aly. “This Awesome App Allows You to Take Perfect Selfies With Your Dog.” Pet Central by Chewy, 6 Dec. 2016, https://petcentral.chewy.com/health-wellness-this-awesome-app-allows-you-to-take-perfect-selfies-with-your-dog/.

“Top Dog Hashtags to Make Your Dog Insta-Famous.” Petfinder, https://www.petfinder.com/dogs/living-with-your-dog/top-dog-hashtags-instagram/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.

What Names Are Allowed on Facebook? | Facebook Help Center. https://www.facebook.com/help/112146705538576. Accessed 11 Oct. 2019.